Why the U.S. Government Never, Ever Has to Pay Back All Its Debt

Governments really can, and do, borrow forever.

(Reuters)

How will our children, grandchildren, and sundry other friends and relatives too young to see an R-rated movie unaccompanied ever pay back the entire debt the government is piling up now? Easy. They won't. The U.S. government is never completely debt-free (except for that one time it sold land seized from Native Americans).

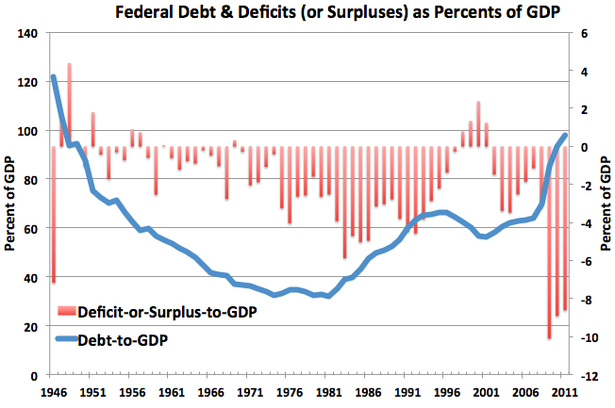

There's only one thing you need to know about the government. It's not a household. The government, unlike us, doesn't need to pay back its debts before it dies, because it doesn't die (barring secession or a sneak attack from across the world's longest unprotected border -- a most unworthwhile initiative). In other words, the government can just roll over its debts in perpetuity. That's the point Michael Kinsley misses when he says we "can't borrow forever," in an otherwise fine column trying to convince unemployment and deficit hawks that they actually agree on a "barbell" approach -- stimulus now, austerity later -- to fiscal policy. We can, and in fact have, borrowed forever. And that doesn't mean our debt burden will go up forever either. As you can see in the chart below, the government dramatically decreased its debt-to-GDP ratio in the three decades following World War II, despite mostly running deficits during the time.

(Note: This chart shows gross debt, which includes debt the government owes to itself, such as the Social Security trust fund. Debt-to-GDP is on the left axis; deficit-or-surplus-to-GDP on the right).

Here's the budget math. Between 1946 and 1974, debt-to-GDP fell from 121 to 32 percent, even though the government only ran surpluses in eight of those years (and the surpluses were generally much smaller than the deficits). That's because nominal GDP -- just the cash size of the economy -- grew much faster than debt did. As Greg Ip of The Economist points out, fast nominal GDP growth, and the easy monetary policy that requires, is the only way governments have ever successfully reduced debt ratios in the past. Austerity alone will fail. (See Europe).

Okay, so maybe endless debt and deficits aren't a problem, but won't bond markets go Galt on us if we don't start to get our fiscal house in order? And even if the bond vigilantes turn out to be more like Godot, won't ever-increasing debt lead to ever-decreasing growth?

Well, as Mike Konczal of the Roosevelt Institute points out, the oft-cited Rogoff-Reinhart 90 percent debt-to-GDP threshold, after which growth supposedly slows, hasn't been proven. It's just a correlation. If anything, it probably gets the causation backwards, with low growth driving deficits and debt, not vice versa. Now, high deficits during high growth could crowd out private investment, and raise interest rates -- the fabled bond vigilantes -- but it couldn't bankrupt us a là Greece. We borrow in a currency we control, so we can never run out of it; we can always inflate as a last resort. This money-printing escape hatch protects us from the kind of self-fulfilling run -- where markets push up borrowing costs on fear of default, which, perversely, makes default more likely -- that had plagued Europe before ECB chief Mario Draghi promised to do "whatever it takes" to save the euro. The worst we have to fear is some kind of replay of 1992, with rising interest payments forcing some combination of tax hikes and/or spending cuts. There's a little bit more to fear than fear itself, but not too much more.

Well, as Mike Konczal of the Roosevelt Institute points out, the oft-cited Rogoff-Reinhart 90 percent debt-to-GDP threshold, after which growth supposedly slows, hasn't been proven. It's just a correlation. If anything, it probably gets the causation backwards, with low growth driving deficits and debt, not vice versa. Now, high deficits during high growth could crowd out private investment, and raise interest rates -- the fabled bond vigilantes -- but it couldn't bankrupt us a là Greece. We borrow in a currency we control, so we can never run out of it; we can always inflate as a last resort. This money-printing escape hatch protects us from the kind of self-fulfilling run -- where markets push up borrowing costs on fear of default, which, perversely, makes default more likely -- that had plagued Europe before ECB chief Mario Draghi promised to do "whatever it takes" to save the euro. The worst we have to fear is some kind of replay of 1992, with rising interest payments forcing some combination of tax hikes and/or spending cuts. There's a little bit more to fear than fear itself, but not too much more.

That leaves us with one last reason to worry, and one not to. Long-term healthcare spending is on an unsustainable trajectory ... but there are some signs it might already be slowing to more sustainable levels. That's the worry. The reason not to is the world's insatiable appetite for our debt. Treasury bonds are a kind of money for the financial system -- shadow banks in particular use them as collateral to fund day-to-day operations -- and they're a kind of money the financial system desperately needs more of now. This brave, new financial world was in embryonic form just 30 years ago, but is so developed today that demand for our debt is much less elastic than you might think.

In other words, don't think of the children. The government should keep borrowing today, and tomorrow, and every day after that. Being a government means you can borrow forever.

Matthew O'Brien is a former senior associate editor at The Atlantic.